Abstract

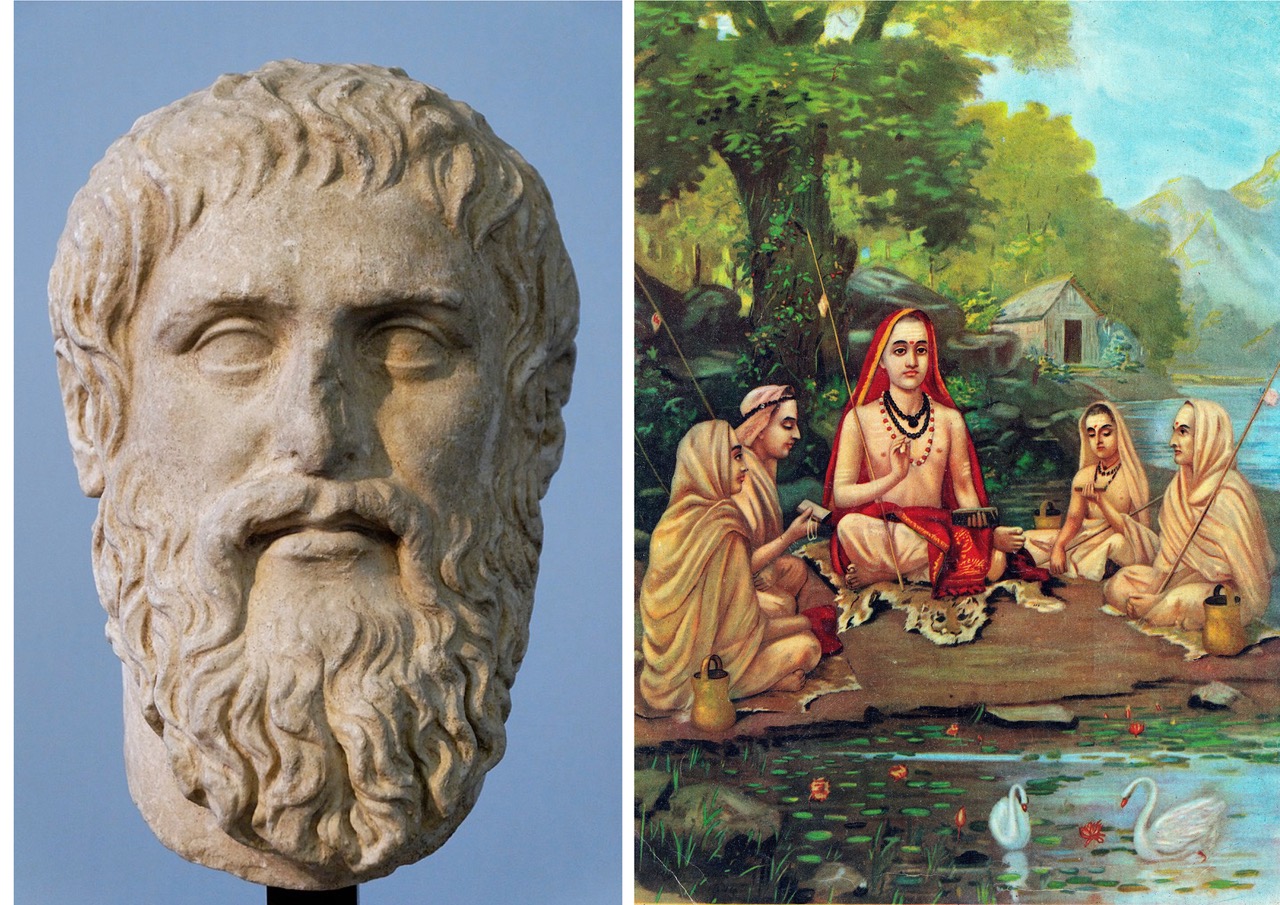

In our inquiry, we investigate the analogies, correspondences, and similarities between Indian Cultural Heritage and Ancient Greek philosophy. Our study deals with the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad as regards Indian philosophy and with Plato’s Phaedrus as regards Ancient Greek philosophy. We concentrate our attention on the image of the individual soul as a charioteer leading a chariot with two horses exposed in Plato’s Phaedrus. This image has strong analogies with the image of the individual contained in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad I, 3. Within this part of our analysis, we investigate the figure of the charioteer and the two horses of the chariot. We point out the difference between the souls of human beings, on the one hand, and the souls of the gods, on the other hand. The allegory of Plato’s Phaedrus proves to be a description of the human condition. The human being is constitutively an imperfect entity: he is exposed to the risk of intellectual and moral decadence. Knowledge of the authentic dimension of the reality is needed in order that the human being could avoid the intellectual and moral decadence. Furthermore, knowledge is necessary for the soul in order that the soul can return to its original dimension. The earthen dimension is not the original dimension of the human soul; it is not a dimension in which the human soul ought to remain. The earthen dimension is a dimension which should be abandoned. The nostalgia for the authentic dimension of reality is one of the characteristics of the soul enslaved in the earthen dimension.

The image of the chariot of Phaedrus has analogies with the Kaṭha Upaniṣad 1.3.3–1.3.9. Through the analysis of the Kaṭha Upaniṣad, we can observe that understanding is necessary for the human being to reach a dimension of reality which is different from the customary life dimension; understanding is necessary for the individual to be free from the chain of rebirths. Constitutively, there can be a contrast between elements composing the human being, i.e. between the intellect and the senses. If the senses are not subdued to a discipline, they hinder the journey of the human being to the authentic dimension of reality. Only the development of understanding can enable the human being to train the senses in an adequate way. In this context, too, the idea is present that the human being should reach a different dimension if the human being wishes to be free from the chain of rebirths; the initial condition of the human being is a condition which should be abandoned. The customary dimension in which the human being lives is not the authentic dimension of the human being.

The image of the chariot introduces us, therefore, to a frame of correspondences between Plato’s Phaedrus and the Kaṭha Upaniṣad which can be listed as follows:

- The customary life of the human being is not the authentic dimension of the individual.

- The human being is, as such, a composed entity.

- Any human being has a plurality of factors in himself.

- The human being is enslaved in a chain of rebirths.

- The enslavement in the customary life dimension is not definitive; an alternative dimension can be reached by the human being.

- Only through a process of education can the human being reach the correct disposition of the intellect.

- Knowledge and understanding are necessary for the human being to be able to lead his life.

1) Preamble

In our study, we are going to investigate some analogies between Plato’s Phaedrus[1] and the Kaṭha Upaniṣad. We shall direct our attention to the presence in both texts of the image of the chariot and to the connection of this image with the individual’s nature. The image of the chariot is used in Plato’s Phaedrus in order to give a portrait of the structure of the individual’s soul. In the Kaṭha Upaniṣad, the image of the chariot is used in order to give a description of the individual’s structure. The image of the chariot introduces the reader to the analogies between the two texts: these analogies regard, for instance, the nature of the human being, the position of the human being in the reality, and the importance of knowledge for the life of the human being. The main aspects which we shall find through the two images are as follows:

- The customary dimension of reality is not the authentic dimension of the human being.

- Elements present in the human being are a problem for the stability of the human being and for his development.

- The human being ought to go to another dimension, i.e., to a dimension in which the human being is free from the chain of rebirths.

Before proceeding to the analysis of the mentioned texts, we would like to begin our investigation with a short quotation from the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, Chapter I, 3, 28. The quotation can be useful in order to show the main concepts of this investigation: the existence of a false and of an authentic dimension in the reality, the individual’s awareness of the existence of the dimension of the authentic reality, and the individual’s wish to reach the dimension of authenticity. The quotation is as follows:

Asato mā sad gamaya /

tamaso mā jyotir gamaya /

mṛtyor mā amṛtam gamaya

From the unreal lead me to the real!

From the darkness lead me to the light!

From death lead me to immortality![2]

[1] As regards Plato’s works, we used the edition of John Burnet, Platonis Opera. Recognovit Brevique Adnotatione Critica Instruxit Ioannes Burnet (5 vols., Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1901–1907).

[2] As regards the translation of the quoted passage of the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad and as regards the translation of the passages of the Kaṭha Upaniṣad which we shall quote in our study we adopted the translation of Patrick Olivelle, The Early Upaniṣads. Annotated Text and Translation.

2) Introduction

As anticipated, we shall base our analysis on the image of the chariot present both in Plato’s Phaedrus and in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad[3]. The aspect from which we begin our analysis is the connection of

the image of the chariot to the human being. In order to give an example of the analogy between Kaṭha Upaniṣad and Phaedrus, we quote the following sentences:

‘Know the self[4] as a rider in a chariot,

and the body, as simply the chariot.

Know the intellect as the charioteer,

and the mind, as simply the reins.’

(Kaṭha Upaniṣad, Verse 1.3.3)

and

‘Let us then liken the soul to the natural union of a team of winged horses and their charioteer.’ (Plato’s Phaedrus, 246)[5]

The themes which we are going to extract from the analysis of the two texts are the following:

- The condition of the human being in the earthen dimension is a condition from which the human being ought to free himself.

- Within the earthen dimension, the human being is imprisoned in the sequence of rebirths.

- Knowledge is the instrument of liberation from the inauthentic condition. In Plato, the kind of knowledge which leads the individual to the liberation from the earthen limitations consists in the knowledge of the realm of Being. In the Kaṭha Upaniṣad, knowledge regards the capacity of the individuals to dominate the influence of the senses.

The mentioned authors give different interpretations regarding the analogies between the image of the chariot in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and the allegory of the chariot in Plato’s Phaedrus. Bucca considers the two images as independent from each other; he points out that the similarities between the two images regard, for instance, the role attributed to the intellect as director of the human being and the necessity of an internal discipline for the spiritual development of the human being (see p. 23). Likewise, Schlieter, analysing the differences between the image of the chariot in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and the allegory of Plato’s Phaedrus asserts that the two images have developed autonomously from each other. Höchsmann points out the presence both in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and in the Phaedrus of a conception of the individual as a composite entity: the unity of the individual represents the moral goal in both texts. Magnone explains the similarity between the images of the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and of the Phaedrus with the influence of Indian Culture on Ancient Greek thought. Ronzitti sees as the cause of the analogies between the two images the belonging to the common Indoeuropean origin of the two cultural traditions.

[3] As regards studies concerning the image of the chariot in Indian Cultural Heritage and in Ancient Greek thought, we refer (in alphabetical order) to Salvador Bucca, La Imagen del Carro en el Fedro de Platon y en la Kaṭha – Upaṇiṣad; Hyun Höchsmann, Cosmology, psyche and ātman in the Timaeus, the Ṛgveda and the Upaniṣads; Paolo Magnone, Soul chariots in Indian and Greek thought: polygenesis or diffusion?, Paolo Magnone, Dio è Verità, la Verità è Dio. Percorsi convergenti del dialogo in Gandhi e Panikkar; Rosa Ronzitti, Platone, l’Oriente, il carro alato, Rosa Ronzitti, Parmenide indoeuropeo. Simbolismo e sacertà del matrimonio nel proemio di Parmenide e in RV X 85; Jens Schlieter, ‘Master the chariot, master your Self’: comparing chariot metaphors as hermeneutics for mind, self and liberation in ancient Greek and Indian sources.

[4] I.e.: ātman.

[5] As regards the translation of Plato’s Phaedrus, we adopted the translation of Plato’s Phaedrus contained in: Plato. Complete Works. Edited, with Introduction and Notes, by John M. Cooper; Associate Editor Douglas S. Hutchinson, Indianapolis/Cambridge, 1997).

- There is a negative factor in the human being; i.e., there is a factor in the human being which hinders the human being from reaching an authentic dimension.

- Depending on the level of knowledge and understanding, there are different dimensions, different ways of life, and different developments of the life of the human being.

- The senses in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and the non-intellectual faculties in Plato’s Phaedrus can be a hindrance for the liberation and for the ascent of the human soul.

- The human being needs to undergo a process in order to reach the liberation from the chain of rebirths.

The images of the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and of the Phaedrus are functional to the process of self-acquaintance. The human being understands through these images the existence of a different dimension from the dimension in which he is living; he understands that there is not only the dimension of the customary reality, i.e., the dimension of the sensible reality. He understands that his authentic dimension does not consist in the sensible reality; therewith, he becomes aware that the meaning of the individual’s existence cannot be explained through the customary reality: something else exists beyond the customary reality.

3) Phaedrus’ image

We come now to the analysis of some aspects of Phaedrus’ allegory. The allegory can teach many elements regarding the constitution of the human soul[6]:

- The earthen dimension is not the only dimension of reality.

- The union with the body is not constitutive for the human soul. The human soul precedes the body; it is originally autonomous from the body.

- The human soul originally belongs to a dimension which is different from the customary life dimension.

- The human soul can fall from its original condition.

- The earthen dimension of the human soul is a fall from its original dimension.

[6] The fact that Plato resorts to a myth in order to describe the soul does not mean that we cannot extract elements from the myth: these elements prove to be useful in order to understand the constitution of the soul as such. The contents of the allegory can be translated into dispositions and conditions of the human soul. The myth gives us elements for the comprehension of the human soul as regards, for instance, the structure of the human soul, the limits of the human soul, the danger of decadence of the soul, and the role of knowledge in the development of the human soul.

- The human soul can belong again to a dimension which is alternative to the customary life dimension. The presence of the human soul in the earthen dimension is not a definitive condemnation.

- After the decadence of the human soul, the human being is enslaved in a dimension of rebirths.

- Philosophical knowledge is the way of liberation from the chain of rebirths.

- The non-intellectual dimension of the human soul ought to be disciplined.

- There is a constitutive difference between the gods’ souls and the other souls.

- The human being is constitutively a limited entity.

- The human being cannot go beyond his own limitations, but he can develop himself within a certain range of possibilities.

- The human being is able to reach a condition different from the condition in which he is living if he decides to follow the road of knowledge. Decadence is not an immutable fate: it will come about if there is no knowledge. The human being can reach a different dimension from the sense dimension if he reaches the philosophical education.

Let us read now some aspects of Plato’s allegory[7]. In Phaedrus 246a2–b4 Plato tells:

‘That, then, is enough about the soul’s immortality[8]. Now here is what we must say about its structure. To describe what the soul actually is would require a very long account, altogether a task for a god in every way; but to say what it is like is humanly possible and takes less time[9]. So let us do the second in our speech. Let us then liken the soul to the natural union of a team of winged horses and their charioteer. The gods have horses and charioteers that are themselves all good and come from good stock besides, while everyone else has a mixture. To begin with, our driver is in charge of a pair of horses; second, one of his horses is beautiful and good and from stock of the same sort, while the other is the opposite and has the opposite sort of bloodline. This means that chariot-driving in our case is inevitably a painfully difficult business.’

[7] For Plato’s Phaedrus we used the commentary of Ernst Heitsch, Platon Phaidros. Übersetzung und Kommentar von E. Heitsch (Vandenhoek und Ruprecht, Göttingen, 1993).

[8] We shall not deal with the proof of the immortality of the soul in this study, since the inquiry into Plato’s demonstration deserves, in our opinion, an autonomous study.

[9] On closer inspection, Plato points out twice the limitations which are constitutive elements of the human nature. On the one hand, before exposing the myth, Plato contends that it is not possible for us to completely describe the human soul. On the other hand, within the exposition of the myth, Plato explains that the human soul is constitutively limited and is therefore as such not able to have the same vision of the authentic reality as the vision which the gods’ souls are able to have.

After speaking on the immortality of the soul in the passage which immediately precedes the quoted one, Plato proceeds to speak about the constitution of the soul. Plato’s discourse is going to be exclusively a likeness of the authentic structure of the soul. The likeness can nonetheless deliver elements of the condition of the human soul and elements of the dispositions of the human soul. The soul is described as the union of winged horsed, on the one hand, and of a charioteer, on the other hand. This description of the soul holds both for the souls of the gods and for the souls of the human beings. There is, nonetheless, a precise difference between the souls of the gods, on the one hand, and the souls of human beings, on the other hand; the horses of the gods are good, whereas in the case of human beings, whose souls have two horses, only one of the horses is good. As a consequence, the human being will constitutively have problems due to the composition of his soul[10]. From the very beginning of the exposition, the difficulties which are innate to the human constitution are pointed out. Human beings are constitutively inferior to the gods; human beings are not gods.

The chariot driving proves to be for the human beings a difficult enterprise as such. Plato goes on in the exposition of the myth as follows:

‘And now I should try to tell you why living things are said to include both mortal and immortal beings. All soul looks after all that lacks a soul, and patrols all of heaven, taking different shapes at different times. So long as its wings are in perfect condition it flies high, and the entire universe is its dominion; but a soul that sheds its wings wanders until it lights on something solid, where it settles and takes on an earthly body, which then, owing to the power of this soul, seems to move itself. The whole combination of soul and body is called a living thing, or animal, and has the designation ‘mortal’ as well. Such a combination cannot be immortal, not on any reasonable account.’[11] (Phaedrus 246b5–c7)

Plato’s exposition is an explanation of the existence of mortal and of immortal entities. From the description, we can see that the soul takes different shapes in the different places of the reality. The soul takes care of everything that does not have a soul. The theme of the loss of the wings is introduced: the human soul can fall; i.e., it is possible that the human soul does not remain in the same condition in which the human soul was originally. The condition of the human soul is not immutable.

Souls which lose their wings are united with a body. Bodies seem to move themselves; actually, the souls which are in the bodies are the cause of the movement of the bodies. The cause of the loss of the wings is not yet explained. The union of a soul and a body is defined as a living being or as an animal. The birth of a living being is therefore due to the fall of the soul. The composition of the soul and the body cannot be immortal. Plato goes on in his exposition of the image as follows:

‘In fact it is pure fiction, based neither on observation nor on adequate reasoning, that a god is an immortal living thing which has a body and a soul, and that these are bound together by nature for all time — but of course we must let this be as it may please the gods, and speak accordingly. “Let us turn to what causes the shedding of the wings, what makes them fall away from a soul. It is something of this sort: by their nature wings have the power to lift up heavy things and raise them aloft where the gods all dwell, and so, more than anything that pertains to the body, they are akin to the divine, which has beauty, wisdom, goodness, and everything of that sort. These nourish the soul’s wings, which grow best in their presence; but foulness and ugliness make the wings shrink and disappear.’ (Phaedrus 246c7–e4)

The good condition of the human soul in the reality is not given once and for all. The earthen existence is, actually, a fall from the original condition of the human soul. The earthen life of the human soul corresponds to a condition of decadence of the human soul from its original condition. Thus, the earthen condition of the human soul is not the original dimension, but a derived dimension for the human soul. Moreover, the earthen condition is not the immutable condition of the human soul; through an appropriate formation, the human soul can go back to its original dimension.

[10] Plato aims to point out this difference from the very beginning of his exposition of the allegory. The human soul constitutively has difficulties; this condition of the human soul is independent of the human soul’s being tied to a body. The union of the body is not the cause but the consequence of the constitutive difficulties of the human soul.

[11] One of the aspects of the allegory is that the soul is independent of the body; the soul is not to be defined for its relation to the body. The union with the body is accidental; the soul as such precedes the body and the whole sphere to which the body belongs. The soul seems to be tied to the body; actually, its original dimension is free from the body.

end of part 1 of 3

part 2 is here

part 3 is here

Autori: Bouvot Kathrin – Segalerba Gianluigi

Bravi!

Ottimo progetto.

Grazie mille Giuseppe.

Riferiremo all’autore il tuo complimento.

La Redazione di Progetto Montecristo