The language of the Science of the Cosmos

Contemporary philosophy has had the merit of emphasizing the importance of language – its ambiguity and its richness. We can also say that, to a certain extent, a language is a theory about the world (and about us). A way of representing the world that is also linked to the ontological content of what we say.

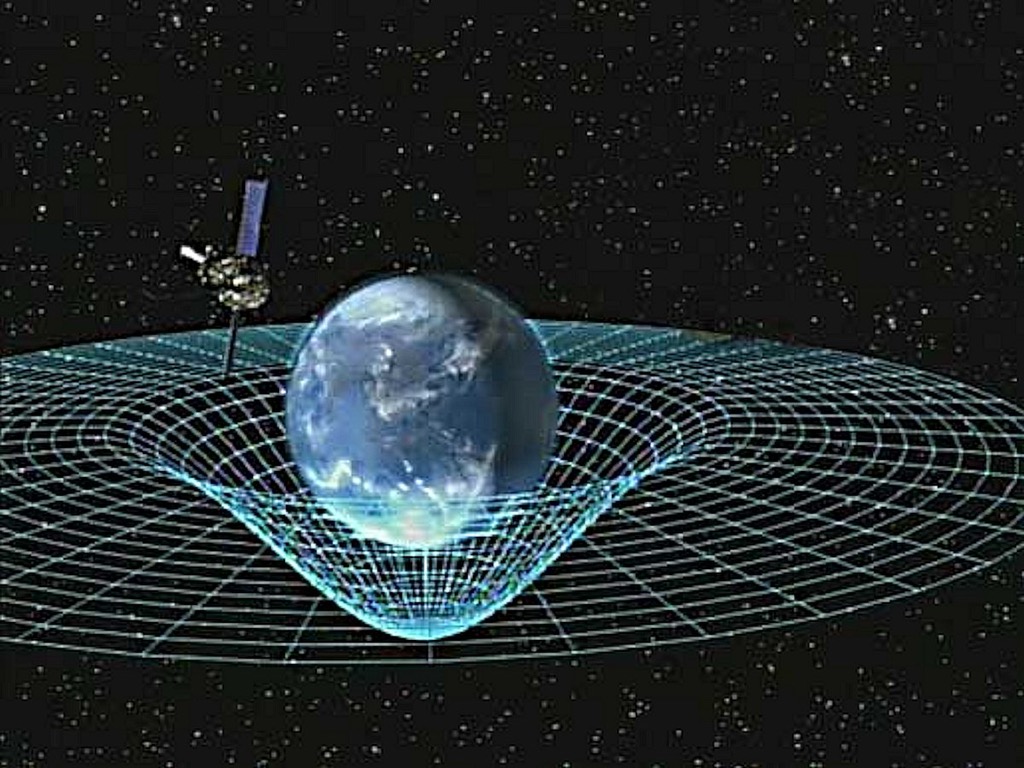

Thus, in moving from Newtonian gravitation to the new theory of gravitation, General Relativity, we change both the formal description of the world and the language we use to describe it.

Newtonian gravitation is based on the principle of action in a vacuum at a distance. Newtonian force is therefore an action that is transmitted at infinite speed… and moving (as if by magic) the position of a planet in the solar system would instantly give rise to a repercussion, a change, at a distance of billions of light years in the Universe.

Einstein gravitation is instead based on the idea of space-time curvature. If we move a planet in the solar system, we are changing the curvature of space-time and that change will propagate through the Universe (in the form of a gravitational wave), arriving a billion years later to have an influence on something that is a billion light years away. We have changed the language. And not only that, we have also changed the characters, the ontology of the theory: from a world of masses and forces we have moved to a world of energies, curvatures of space-time and gravitational waves.

Regardless of whether General Relativity can be considered more effective than Newton’s old theory (in fact it is), we are interested in the change of principle. Another principle is leading us in another direction and even seems to describe facts that are different from the previous case. For this reason, for example, we must be cautious in calling a part of the path of science a principle. Because science is flexible in this aspect, willing to modify and abandon, to leave one principle for another. Because in the end the deepest and most resistant principle of science is not a “scientific” principle, but an ethical one: the search for truth. Only that.

Fig. 1 – Portrait of Luca Pacioli, by an uncertain author, perhaps Jacopo de’ Barbari (circa 1500). The figure on the right could be Copernicus.

New languages open new horizons, and in fact we owe to astrophysical knowledge the possibility of studying the cosmos. Of studying our galaxy, of studying other galaxies. The possibility of studying planets, not just the planets of our “little town”. Our solar system, a little town ten billion kilometers big, but still small compared to our galaxy.

There are many other planets, planets that rotate around other suns and we want to study them. We also want to analyze their atmospheres, and hypothesize the forms of life that they can host. And this conceptual space was also opened by the Ancients, from Democritus to Epicurus. Our Universe appears – and was actually called that way – a World of Worlds [1].

We do not know what the life forms that – in all likelihood – inhabit other planets are like. It is difficult to think of communicating with them, given that in the best case our greetings would not be answered for eight years. This is the “best case” because we know – or think we know – that the maximum speed of propagation of anything does not exceed that of light in a vacuum and the closest star to us is four light years away.

[1] The hypothesis that other inhabited worlds existed was already present in the philosophy of the ancient Greeks (Anaximander, Epicurus) and was then taken up by many wise men and philosophers over the centuries. In particular, Kant supported the hypothesis that the Milky Way (the only known galaxy at the time) was a “world of worlds”.

Autori: Marco G. Giammarchi e Roberto Radice

0 commenti